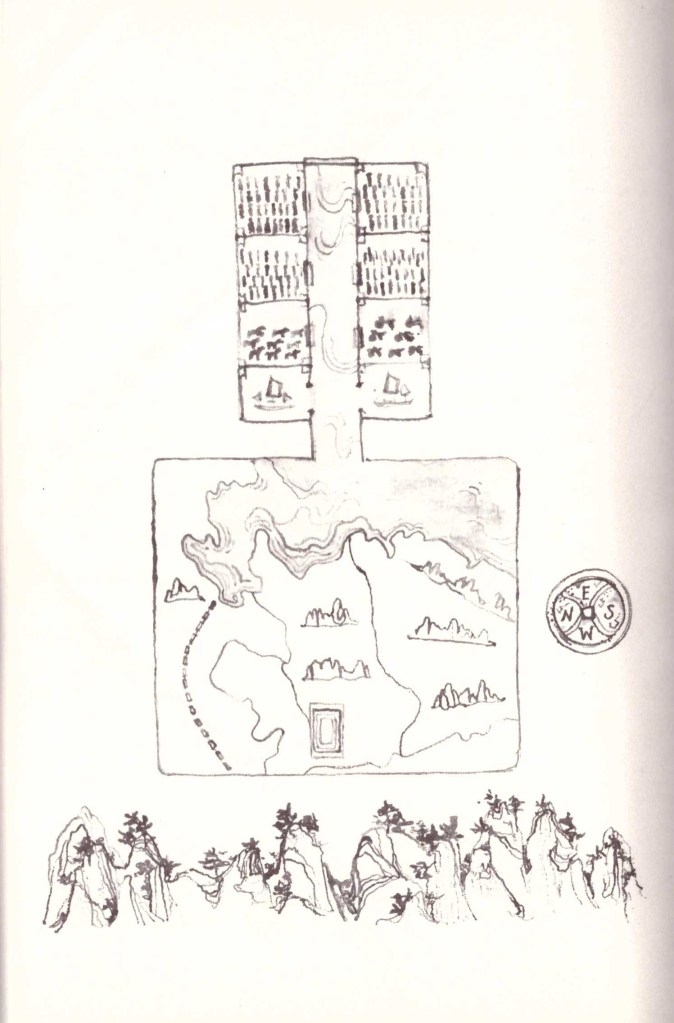

[This is a translation of an article by Caroline Duvezin-Caubet originally written and published in French: « La carte du cœur : Navigation magique et identités postcoloniales dans The Girl From Everywhere de Heidi Heilig » (Mondes et cartes : Les chantiers de la création n°10, Aix-en-Provence, Presses Universitaires de Provence, 2018 [ISBN 9791032001585], p.87-103), downloadable below. The paper from which it stems was originally presented in April 2017 – as a result, there are several points and formulations which I don’t necessarily agree with anymore, but apart from some slight rephrasing, the translation of the main text is meant to match (the footnotes do not, and the original obviously had no gifs). The maps are from the Hot Keys Books edition quoted in the bibliography.]

Abstract: Imaginary maps are a major generic marker for contemporary fantasy, and are often studied for how they participate in the poetics of world-building, but rarely called into question for the imperialistic dimension of cartography. Heidi Heilig’s 2016 The Girl From Everywhere fills that gap with a pirate captain who can Navigate his ship magically through the seas and the centuries, but whose real goal is to return to Hawaii in 1868, to save his wife before she dies giving birth to their daughter – which may very well cost the latter’s existence… The book’s magic maps raise complex postcolonial questions around the island’s fading paradise, and show how, by intermingling political and personal issues, fantasy can be a way to participate in real-world problems rather than escape from them, which seems crucial in Young Adult literature.

Introduction

There are relatively few imaginary worlds which are mapped out. Indeed, the map forces upon the reader a definitive form/image and reduces their margin of interpretation/autonomy. It will therefore only be found when the work shows a systematic, demiurgical will to build a coherent world which competes with the real world. (Jourde 103)[1]

The fact that The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings feature as sole representatives of the fantasy genre within Pierre Jourde’s 1991 book about imaginary maps is at once surprising and inevitable. Inevitable because J.R.R. Tolkien, often seen as the father of modern fantasy, remains a major landmark: Peter Jackson’s adaptation to the big screen played a major role in making the genre familiar to the wider public at the beginning of the 21st century, and The Lord of the Rings established the tradition of pseudo-documentary appendixes, among which the geographical map is, according to Anne Besson, by far the most durable and exploited (Besson 149).[2] Surprising because, in the United Kingdom and United States, the critical study of imaginary maps starts as soon as 1973[3] and covers a much wider sample than Tolkien, according to Stefan Ekman’s literature review (Ekman 15-19). French scholarship in speculative fiction is always a bit behind – however, the different books quoted by Ekman seem to be just as focused on the poetics of worldbuilding as Jourde, leaving the political aspect largely to the side. The map, despite being described as the perfect instrument for domination (Jourde 103),[4] one which “imposes order and gives orders” (Rivière 379),[5] is almost never put in question as an imperialistic tool, and appears moreover rarely as an actual object handled by the characters in the many fantasy novels which place it on their narrative threshold.[6]

The Girl From Everywhere (2016), Heidi Heilig’s debut novel, does not follow that trend. Her heroine Nix Song lives aboard a pirate ship, The Temptation, which her father and captain, Slate, can Navigate to any place and any time (including imaginary ones) as long as he has an authentic map. Yet the treasure he has been seeking for sixteen years is not a magic lamp or a mythical animal: he is trying to return to Hawaii in 1868, to save Nix’s mother, Ling Song, before she dies in childbirth. A secret society, the Hawaiian League, takes advantage of his heart’s desire to offer him a deal: in exchange for this map to the heart, he and his crew will have to rob the royal treasury in 1884, thus hastening the end of the monarchy. In Honolulu, Nix encounters the last king of Hawaii, David Kalākaua (also known as the “Merrie Monarch”) in a bar, and recalls that alcohol will be the death of him, as well as his down-to-earth last words, “Alas, I am a man who is seriously ill” (Heilig 119). The book’s magic system, which allows characters and reader to visit lost worlds, is as much one of twilight as of marvel, and the reflections on postcolonial identity (national and personal[7]) are at the heart of the protagonist’s adventures.

In this article, I want to show how maps in The Girl from Everywhere are not there to “compete with the real world”, but rather to play on the distinction between real and fictional, authentic and fake, ordinary and extraordinary. The novel’s metafictional and postmodern games around this tool for representing the world show the link between the poetics of writing and the author’s political, anti-imperialist stance.

I – Beginning(s) and end(s): from lost origins to horizons of failure

Analyzing the first chapter of the novel, and especially the incipit and the end of said chapter, shows clearly how Heilig plays with our expectations, shifting our reading perspective from linear to circular mechanics.

1. A shifting incipit

It was the kind of August day that hinted at monsoon, and the year was 1774, though not for very much longer. I was in the crowded bazaar of a nearly historical version of Calcutta, where my father had abandoned me.

He hadn’t abandoned me for good—not yet. He’d only gone back to the ship to make ready for the next leg of the journey; twentieth-century New York City. It was at our final destination, however, where he hoped to unmake the mistakes of the past.

Mistakes like me, perhaps.

He never said as much, but his willingness to leave me behind was plain: here I was, alone, haggling for a caladrius with a pitiful amount of silver in my palm. Part of me wondered whether he’d care if I returned at all, as long as the mythological bird was delivered to the ship.

No, he would care, at least for now. After all, I was the one to plot our way through the centuries and the maps, the one, who helped him through his dark times, the one who could, say, identify fantastical animals from twenty paces and negotiate with their sellers. Then again, once we reached 1868 Honolulu, he would have no need for navigating or negotiation. I was a means to an end, and the end was looming, closer every day. (Heilig 1-2)

The novel opens on a map of India in 1774 [see Map 1], a time and space which are reiterated immediately in the first sentence, but indicated as temporary with the last clause. Temporal adverbs and expressions (“not for very much longer”, “not yet”, “for now”) are used all through the extract to guide our expectations, which are far from clear or reassuring, and become very dark once the nominal group “our final destination” is used. It seems that Nix is alluding to a much more deadly kind of end than simply coming into port. The supernatural aspect is introduced progressively: the passing remark on the imminent end of 1774 has a rational explanation (which is that we are on the brink of 1775), but the expression “a nearly historical version of Calcutta” is almost oxymoronic. The final mention of “twentieth-century New York City”, after a semi-colon which underlines the break typographically, makes the existence of time-travel the only logical explanation without having to explain the process. The zeugma “to plot our way through the centuries and the maps”, which plays on the narrative/geographical polysemy of the verb “to plot”, helps to blend the notions of time and space.

The incipit plays upon small breaks and tiny cracks to convey worldbuilding and personality: the information conveyed by the auto-diegetic narrator about her tense relationship with her father is immediately contradicted, then further nuanced, forcing the reader to go back and forth in their assessment of the father-daughter bond. The line breaks, especially at the end of the first paragraph and for the lone line that is the third paragraph, feed into the dramatic tension and guide the reader’s eye, trained not on marvelous elements like the caladrius (a “genuine” mythological bird from the Middle Ages with healing powers), but on the narrator’s inner torments and her abandonment issues. As she lists her abilities, the ternary rhythm of the anaphora (“I was the one who… the one who… the one who…”) establishes her legitimacy as the exceptional protagonist, but also underlines her loneliness. In the third paragraph, the adverb “perhaps”, thrown in after the comma like a stray thought, seems to put into question not the whole notion of the heroine as a mistake, but her sense of self and her very existence. This impression is emphasized in the last paragraph with the alliteration in [n] (“no need for navigating or negotiation”). The metaphor “I was a means to an end” makes Nix appear like nothing but a tool, a pawn on the chess board of her life, in an inversion of the natural order: indeed, if Slate manages to save Lin, their daughter might disappear, as if the child was a necessary sacrifice to bring her mother back to life. While it projects the reader into a magical time and space, this incipit is extremely dark, especially for a YA novel.

2. Great expectations and false promises

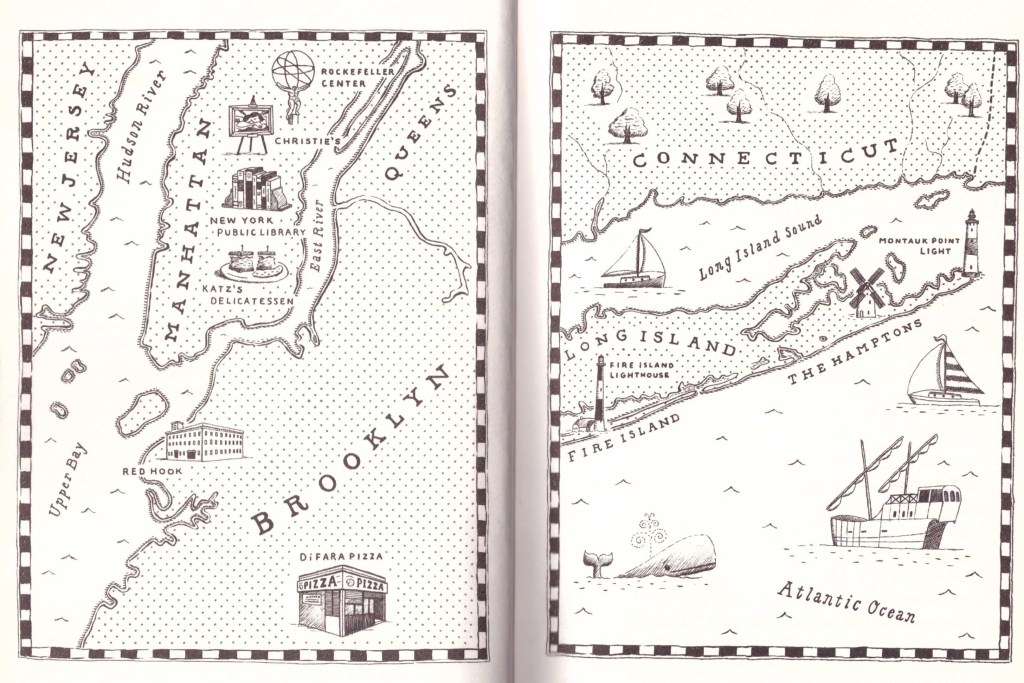

Moreover, this macabre set of expectations, which feeds into the narrative and emotional tension, also plays on the limits and edges of maps. A few pages later, Slate tries to take his crew into the second map mentioned in the incipit, New York in 1981 [see Map 2], which has a different iconographic style. The characters then remain suspended for several paragraphs in the Margins (a space between maps which Nix compares to purgatory) before going overboard with a lovely phrasal verb which conjures up old flat-earth models: “as we ran right off the edge of the map” (Heilig 12).

The universe established by the incipit is unstable and precariously balanced. The first map introduces the time and space of the story, but only for one chapter, and the second map, slipped in between chapters 1 and 2, fails: the pirate ship does arrive in New York, but in 2016 (which is to say the time and space where Slate would be living if he wasn’t time-traveling, and which emerges at the edge of every map for him). Each of these maps therefore sets up a false promise as far as reading expectations go. Why the second map failed will only become clear to the characters much later in the novel, although it is only logical: a Navigator cannot go to a time and space in which they already exist. Therefore, every map to Honolulu in 1868 will fail as long as Slate has Nix on board, since she already exists within her mother’s womb in that time and space. He has to choose between his wife and his daughter: the quest for a family idyll is doomed to failure, and seems like a lost paradise. It’s as if the origin and the goal of the narrative set in motion in the first chapter cancelled each other out, dragging the reader into a circular journey over troubled waters, where they cannot trust their usual landmarks.

II – (Un)real Signs: Dates, Names and Bodies

This deconstruction of temporal and spatial landmarks is repeated in a more concrete manner within the textual and visual space of the map, through the different signs which “anchor” the Navigation and its reality, starting with the date.

1. Forged dates and body maps

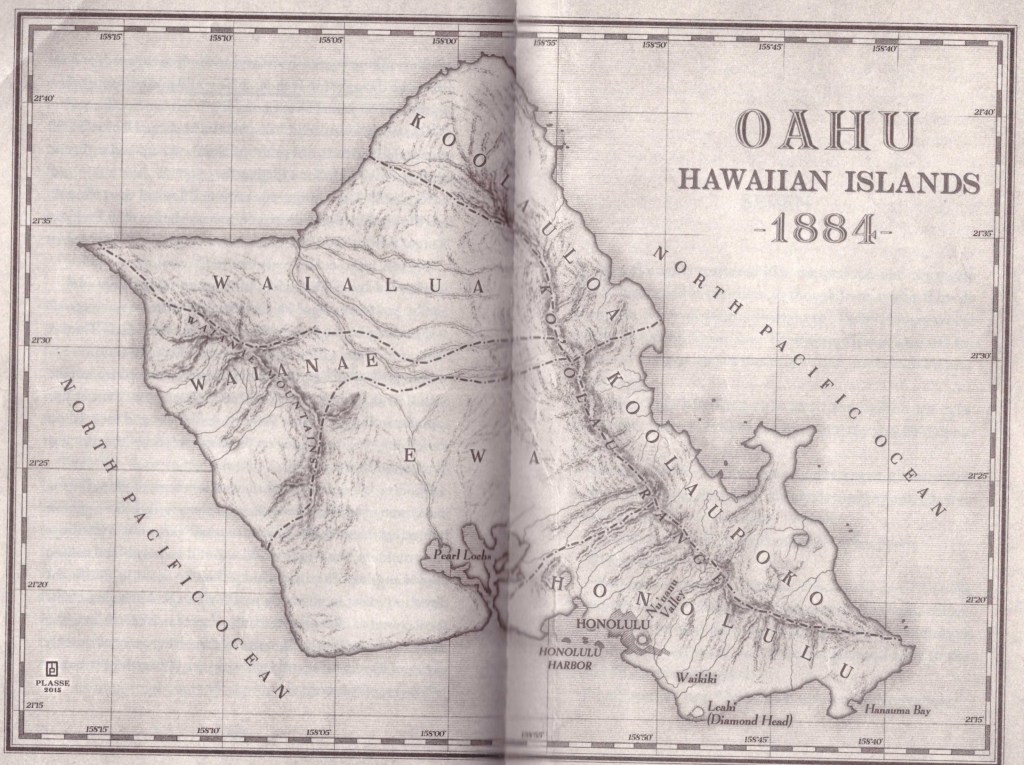

According to the rules of the magic system, a map can only be used once and needs to be authentic, which is to say drawn by hand but also truly from the time it pictures. Slate buys a map of Hawaii in 1868 during an auction in 2016 New York, and that map does take him to the desired space, but not exactly at the right time: most of the story takes place in 1884. That map had actually been commissioned and wrongly dated by the Hawaiian League, to bait Slate. This forging is echoed in the break between image and text, since the third appendix-map shown to the reader, Oahu in 1884 [see Map 3], does not fit the description given by the narrator. Indeed, as Nix is reviewing the map to find any mistakes, she remarks upon the presence of Honolulu’s main street names (Heilig 51). This is important because the more details a map has, the greater the chance of its authenticity, but the scale of the appendix-map is much too big for that kind of annotations. Moreover, Nix notes that the city is centered on the Iolani Palace, where the king lives, but only remembers two chapters later that said building was build between 1879 and 1882: focused as she was on the date, she actually saw the signs of forging but didn’t notice them (72-73). This gap in perception reflects the lack of continuity between the text and its map appendixes, which encourages characters and reader to treat geographic and historical landmarks as ciphers and codes to be cracked.

The authentic map to 1868 which the League intends to sell to Slate, when it finally appears (described textually, not as an appendix), once more subverts our expectations: it is not dated and the amateur cartographer, Blake Hart, referenced the bars, brothels and opium dens on it (128). However, these scandalous landmarks actually allow for the authenticity of the map to be established: the League representative points out to Nix and Slate that Joss’s apothecary/opium den changes names in 1868 to reflect the condition of the young woman living there. The den is marked as “Hapai Hale” on this map, and will later become known as “Happy House” to ignorant tourists (129). The tragic irony of this distortion (as the young woman is of course Lin, and “hapai” means “pregnant” in Hawaiian) seems to stage the erasure of the conquered body, language and land that colonialism enacts, and triggers an epiphany for Nix:

Hapai Hale. The very first hint of my existence was marked on the page. I was written into that map as a landmark. Before I’d even known it, I’d been a part of this place, and it was increasingly hard to pretend that it wasn’t a part of me. Something of it lived under my skin, indelible as a tattoo.

It was the home that might have been, and for the first time, I felt the loss of it—the world where my mother lived and my father stayed in Hawaii and I grew up within the boundaries formed by the golden line of sand encircling the island. But who would I have been in that version of reality? Me, or not me? (Heilig 178-179)

Before she was even born, Nix was a toponym, and that passage plays upon utopia[8] (“no place”) and uchronia, since the modal “might” and the past perfect sketch out a world where everything it at once possible but also already lost. Nix, “the girl from everywhere”, is nowhere at home, and her polysemic name reflects her torn identity.

2. What’s in a name?

The heroine introduces herself several times by explaining that the nix is a nymph from German folklore who seduces men to drown them, but also gets told repeatedly that nix means “nothing”. When Joss does a numerology reading for her, she notes that in Mandarin, the mirror image of her name, xin, means “happiness”, and that Nix’s number is five, wu, which means both “me” and “not” (101)[9]. “Slate”, with the automatic association to “blank slate”, is a terribly ironic name for Nix’s father, a character defined by his inability to reinvent himself and mourn the past. He is a drug addict, his arms covered in needle marks[10] and tattoos, with his daughter’s name on one wrist and his wife’s on the other (189). He is torn in two in body and mind: Heilig wrote him as a bipolar character (hence the mysterious “dark times” alluded to in the incipit). Is it necessary to rewrite one’s past? Is it possible to choose one’s future? The polysemic names reflect the complicated relationship that all the characters, and Nix most of all, have with Fate – a concept which is central to the fantasy genre.[11]

The two boys warring for Nix’s heart also have very symbolic names: on the one hand, there is Blake Hart, a young Englishman who has lived all his life in Oahu and is the son of the novel’s main antagonist, named after his late and scandalous uncle (who turns out to be his biological father), and whose family name is of course a homophone for “heart”. On the other hand, there is Kashmir (bearing a geopolitically conflictual name), who stole aboard the Temptation in the port of Vaadi Al-Mas, a city from the story of Sinbad in The Thousand and One Nights. The map which Slate used to access that city was based on Antoine Galland’s 1704 translation: Kashmir “oriental” identity, three times removed from reality, is a vertigo-enducing mise en abyme of how much fantasy plays into real life.[12] His French, Arabic and Persian phrases are part of thoroughly polyglottal text, where plays on words, on sounds, on etymology and translations are part and parcel of the semantic weave. Faced with forged or incomplete maps, the reader shifts their attention to the relationships that link the characters to each other and to their respective fates, a network which leads and structures the story’s direction. The inner world matters more than the outside.

III – An Inner World: Beliefs, References and Images

During the novel, the negative space left behind by the defective maps is taken over by a network of echoes which range from intimate to literary and mythical, and redefine the poetics of the marvelous with a lot of nuance.

1. Legendary, Paradoxical Archives

Nix, who is both a 19th and a 21st-century girl, wants to learn to Navigate so she can go back to the age of exploration, fleeing the destruction of the past that globalization brings with it. The name of the pirate ship symbolizes this temptation of going back, and the ship itself is filled with marvels and wonders which the crew brought back from fantastic places[13] : a bottomless bag from Welsh mythology, the “sky herrings” that make up the aurora borealis in Scandinavian folklore, or even maps from countries which only ever “existed” in humanity’s collective imagination and for a brief time, like Crockerland. However, since each map can only be used once, traveling to a legendary place to bring back a souvenir, a relic also means destroying it (at least this particular version) forever.

The loss of the past is treated as inevitable, especially by Slate who, despite his obsession with bringing his wife back to life, states than he cannot imagine a version of reality where the Hawaiian monarchy survives (190). However, these wrongly dated, forged, and doomed maps also play a part in preserving the island’s pre-colonial heritage. Hawaii is compared several times to the garden of Eden; the atmosphere and the landscape descriptions play an important role in the storyline. Blake, who acts as a local guide for Nix, tells her the legend of the Hu’akai Po, an army of ghost warriors who appear at night, signaling their presence with drums. The plan for the heist relies on the fear that the Hu’akai Po evoke, which is supposed to keep the inhabitants indoor while the robbery is taking place. The ploy works, but at the end of the novel, the warriors actually appear. Indeed, to allow Nix and Kashmir to come back from the Chinese Emperor’s tomb with their clay soldiers,[14] Blake draws as accurate a map of 1884 Oahu as he can, adding in for example ruin names and the tomb of Princess Pauahi, who just died in October (252-254). At first glance, the version of Hawaii to which they return in the same one they left, but Blake doesn’t know that he actually believes in the Hawaiian legends he grew up with. The resurrection of the island’s folklore cast the story in an uncanny atmosphere, [15] even though the magic spring which saves Blake’s life certainly comes in useful.

A map’s authenticity cannot be measured objectively. It depends on the faith of the cartographer, an aspect which is also central to Navigation: Slate tells Nix that he can only go a place he believes in (54). Writing and reading maps relies on the “willing suspension of disbelief” that Samuel Taylor Coleridge theorized for poetry,[16] a concept generally used to define the marvelous in general and fantasy in particular. But in this novel, other forces come into play to materialize the fictional world: Nix’s historical, literary and mythical erudition is constantly surfacing, and she ends up correcting another character as they are misquoting a canonical poetic text.[17] The Temptation’s loot and crew are very eclectic, reflecting the pirate-like postmodern intertextuality that permeates the narrative, and which seems at first glance in contradiction with the kind of immersion that the marvelous requires, since it constantly draws us back to the real world.

2. Images and Imagination

It’s striking, for example, how often mythical references are used to describe elements which are not supernatural as such, for instance during a tender moment between Nix and Kashmir:

His breath was warm on my neck, and I shivered again, but not from fear. For a moment, all I wanted in the world was to turn around, like Lot’s wife, like Eurydice, to see what was in his eyes, but before I could gather the courage, he gave me another squeeze and dropped his arms. I sighed with regret, and with relief. (Heilig 122)

The two myths conjured up here[18] warn against the danger of looking back and of trying to bring the dead back (which is precisely what Slate is trying to do): the tragic transgression to the divine order magnifies the heroine’s confused teenage feelings, giving a cosmic dimension to the intimate sphere.

All throughout the novel, Heilig resorts to memorable comparisons and metaphors to express emotions caused or felt by the characters: “Despair had […] settled, like a vulture, onto Slate’s [shoulders]” (40). This simile is particularly interesting because of how the vivid depiction of the character’s depression intersects with the way Heilig describes her own bipolar disorder in an interview: this hypersensitive perception of the world[19] shines through into her speculative writing. French writer Serge Lehman very poetically designates science-fiction (and I’m applying this idea to its fantasy sibling) as the genre where metaphors are reified, “this blinding, vertigo-inducing experience that occurs when among all the possible meanings of a metaphor […], the most objective, the most literal, the flattest – so the one which holds the most potential for logical developments, in short, the most unexpected one – is the meaning which creates the fictional world” (Lehman 24:18-24:34).[20] In The Girl from Everywhere, Navigation embodies and problematizes our fascination for the Othered space of marvelous maps, but parallel to this reified metaphor, the novel sets up a whole network of images which remain “simple” lexical devices, and where the lexical field of navigation is used to picture Nix’s confused feelings for Kashmir and Blake:

And in that moment, I saw the horizon unbounded and I reeled with the vastness of it. What new shores would I discover if I could travel those few inches?

I was a closed book, a rolled map, a dark territory, uncharted; I was surprised by my urgency, but after all, to be known was to exist. (Heilig 145; 251)

The vocabulary choices help to reinvent this tired YA cliché that is the love triangle, since the narrator’s hypersensitivity and her teenage seduction games also express a deep identity crisis. Kashmir, the thief with a heart of gold from One Thousand and One Nights, and Blake, the young Englishman who lived in Hawaii his whole life, represent different facets of what Nix could have been, what she could yet become, and her hesitation between the two boys embodies the postcolonial exile in which her torn self exists. Nix quotes to herself an Arab proverb, “jealousy is nothing but a fear of being abandoned” (217). And the incipit tells us that the most important man in Nix’s life is her father: the story and the world emerge around their broken family unit, around their tragic and heroic quest for a map to the heart.

Conclusion

I believe that The Girl from Everywhere is one of the best answers that contemporary fantasy can make to its reputation as escapist literature. Tolkien’s reaction in “On Fairy Stories”, proudly claiming how natural it is to want to escape the prison of reality, or at least dream of something beside walls and bars, is well-known (Tolkien 79). Heilig chooses to extend reality, while reminding us, through Slate explaining Navigation, that every escape comes with a price,[21] that dropping anchor on a new shore can only occur if we first raise the one holding us to our past. Throughout the novel, Nix tries to define what her own reality is, to balance out the tension between the different ties of her postcolonial identity, and in the process, she guides the reader through a narrative with different levels of interpretation. The magic map, a playful invitation to have marvelous adventures, is also a way to depict the destructive temptation of rewriting history (national and personal), and constitutes an interesting twist on the “texts” which bind history and fiction in postmodern theory.[22]

The time and space setting chosen by Heilig is particularly suited to such questions, since Nix discovers Hawaii at a turning point in its history, caught between desperate attempts to preserve its paradise and the imperialistic appetites of foreign powers: the role of the British Empire in the fall of the monarchy is explicitly addressed, but the seizure by the American government, which is formalized in 1898, is actually already underway economically (Haley xii). The author manages to personalize this geopolitical conflict through her narrator’s very personal connection to the worlds colliding for the fate of the island. Nix also reflects Heilig’s own identity. Like her heroine, she is hapa-haouli (a biracial Hawaiian with a Chinese and a white parent) with a German-sounding name. Contrary to Nix (but just like Blake), she grew up in Hawaii within the island’s landscapes and folklore. Her bipolar disorder is explicitly portrayed in Slate, and her pansexuality, in a more subtle way, in Kashmir. Heilig talks freely about these difference facets of the identity of social media, where she calls for more diversity in YA literature.

In September 2015, author Corinne Duyvis launched the hashtag #ownvoices on Twitter, which is meant to uplift fictional works where authors portray their own experience as members of a minority within their characters. Her own definition was quite broad, and the works which appear under the hashtag on Goodreads include gender, sexuality, ethnicity, race, handicap… This mobilization is part of the conversation instituted after RaceFail’09 in regard to representing the Other in speculative fiction, and shows how the ‘incessant recycling’ that makes fantasy postmodern (Besson 23) also makes it political. The map to the heart is an invitation to go to other lands and to understand Otherness, a message in a bottle cast out to sea in the hopes of changing the world.

Bibliography

Ashcroft, Bill, Griffiths, Gareth et Tiffin, Helen. The Empire Writes Back: Theory and Practice in Post-Colonial Literatures. 2nd ed. London: Routledge, 2002.

Besson, Anne. La fantasy. Paris: Klincksieck, coll. « 50 question », 2007.

Crackower, Marion. « Les cartes et la représentation spatiale dans la fantasy épique : continuité et rupture de l’héritage tolkienien ». Fantasy Art and Studies N°1 (November 2016), p. 42-47. Last accessed 27 novembre 2016, http://fr.calameo.com/read/0049974313af08b5d8df5

Crowe, Jonathan. “Why Fantasy Maps Don’t Belong in the Hands of Fantasy Characters”. Tor.com. 28 May 2019. Last accessed 12 July 2020, https://www.tor.com/2019/05/28/fantasy-maps-dont-belong-in-the-hands-of-fantasy-characters

Coleridge, Samuel Taylor. Biographia Literaria. 1817. Project Gutenberg, 2004.

Duyvis, Corinne. “#ownvoices”. Corinne Duyvis : Sci-Fi and Fantasy in MG and YA. Last accessed 22 April 2017, http://www.corinneduyvis.net/ownvoices/

Ekman, Stefan. Here Be Dragons: Exploring Fantasy Maps and Settings. Middletown: Weslayan University Press, 2013.

Haley, James L. Captive Paradise: A History of Hawaii. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2014.

Heilig, Heidi. The Girl from Everywhere. London: Hot Key Books, 2016.

Ho, Elizabeth. Neo-Victorianism and the Memory of Empire. London: Bloomsbury, 2013.

Hutcheon, Linda. “Historiographic Metafiction: Parody and the Intertextuality of History”. O’Donnell, Patrick et Davis, Robert Con (ed.). Intertextuality and Contemporary American Fiction. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press, 1989, p.3-32.

Jourde, Pierre. Géographies imaginaires : de quelques inventeurs de mondes au XXème siècle. Paris: José Corti, 1991.

Lehman, Serge. “Pour une définition auto-théorique de la science-fiction”. Le mois de la science-fiction à l’ENS. 12 May 2016. École Normale Supérieure de Paris. Last accessed 15 December 2016, http://www.diffusion.ens.fr/data/video-wmv/2006_05_12_lehman_adsl.wmv

Marieke. “DiversifYA : Heidi Heilig”. DiversifYA. 25 March 2015. Last accessed 22 April 2017, http://www.diversifya.com/diversifya/diversifya-heidi-heilig/

Post, Jeremiah Benjamin. An Atlas of Fantasy. New York: Ballantine, 1973.

“Race Fail ’09”. 15 November 2016. Fanlore. Last accessed 22 April 2017, https://fanlore.org/wiki/RaceFail_%2709

Rivière, Jean-Loup. « La carte et la décision ». Cartes et figures de la Terre : [exposition] Centre Georges Pompidou, [Paris, 24 mai-17 novembre 1980]. Paris: Centre de création industrielle, 1980 :379.

Tolkien, John Ronald Reuel. « On Fairy-stories » in The Tolkien Reader. New York: Del Rey Books, 1966, p.33-99.

[1] “Il n’existe que relativement peu de mondes imaginaires cartographiés. La carte, en effet, impose au lecteur une figure définitive et réduit sa marge d’autonomie. On ne la trouvera donc guère que lorsque se manifeste une volonté systématique, démiurgique de bâtir un monde cohérent qui fasse concurrence au monde réel” (my translation)

[2] Game of Thrones’ famous opening shows off the symbolic importance that maps as narrative thresholds have taken on, allowing the viewer/reader to simultaneously enter the imaginary world and orient themselves in it in a very dynamic and visually distinct way.

[3] Jeremiah Benjamin Post, An Atlas of Fantasy (New York: Ballantine, 1973).

[4] “instrument par excellence de domination” (my translation)

[5] “qui ordonne et donne des ordres” (my translation)

[6] ADDENDUM: Crowe lays out a convincing argumentation as to why “fantasy maps don’t belong in the hands of fantasy characters” (see bibliography).

[7] “A major feature of post-colonial literatures is the concern with place and displacement. It is here that the special post-colonial crisis of identity comes into being; the concern with the development and recovery of an effective identifying relationship between self and place” (Ashcroft 8).

[8] Obviously, the “original” utopia (Thomas More’s) was an island, and the island is often considered as an image of the world in medieval studies; I will not dwell on these points here. I will not discuss Heilig’s sequel, The Ship Beyond Time (2017) in detail either in this article, but it should be mentioned that in it, the characters become trapped in a reconstruction of Ys, a famous drowned island of Breton folklore.

[9] Her mother’s number is four, si, a well-known homophone for “death” in Mandarin. That piece of information becomes relevant later when Nix, who does not speak or write the language, has to animate clay soldiers within the tomb of the first Qin emperor. Using the golem as inspiration, she transcribes 54 on their foreheads to make them “not dead”.

[10] Joss predicted that he would die of an overdose a long time ago.

[11] Standing on the prow beside her father in chapter 5, Nix merges the last two lines of ‘Invictus’, William Ernest Henley’s famous poem: “For a moment, I could pretend I was captain of my own fate” (Heilig 29).

[12] He also seems to take on the stereotypical roles of the thief with a heart of gold, and of the heartthrob YA hero about whom readers can fantasize.

[13] Elizabeth Ho sees ships in neo-Victorian fiction as past archives and heterotopias (Ho 176-178).

[14] The tomb is accessed via the fourth and last map appendix [see map 4] of the novel. It has a markedly different iconography than the others, and helps Nix uncover a key part of her family history (which I won’t spoil here). The tomb itself is a mirror image of Hawaii, a dead place designed as a paradise: “Qin thought he’d rest forever in a heavenly afterlife, but the effigy of his empire had faded faster than his crumbling kingdom above. Joss had said it herself. Everything must come to an end. In every myth, paradise is meant to be lost” (Heilig 287).

[15] “Did the healing spring exist before Blake drew it? Had he brought the Night Marchers into being? Was this version of Hawaii the real one, or only a fairy tale he’d told?” (Heilig 335).

[16] “[T]o transfer to our inward nature a human interest and a semblance of truth sufficient to procure for these shadows of imagination that willing suspension of disbelief for the moment, which constitutes poetic faith » (Coleridge loc. 2513-2515).

[17] Oscar Wilde, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, William Blake and William Ernest Henley (see previous note), as far as 19th-century authors are concerned.

[18] However, in this rewriting, it is Eurydice who turns back and not Orpheus.

[19] “When I’m on a high, I’m in love with the world and I can see and do anything and I have so much energy and it feels like nothing will ever end. And when I’m low, everything is so intense—sometimes I get in the shower and shut the door and cry and revel in how raw and deep I can feel despair. It’s beautiful and terrible all at once and very dramatic” (Marieke).

[20] “[L]’expérience de l’éblouissement ou du vertige qui surgit lorsque de toutes les significations possibles d’une métaphore […] c’est la plus objective, la plus littérale, la plus plate, donc la plus riche en développements logiques, la plus inattendue en somme, qui engendre le monde de l’œuvre” (my translation)

[21] “Once you know where you’re going, and you’re sure it’s there, you have to let go of where you’re from. You look straight forward, you keep the land ahead in sight, and you don’t look back” (Heilig 259)

[22] “[B]oth real and imagined worlds come to us through their accounts of them, that is, through their traces, their texts. The ontological line between historical past and literature is not effaced […], but underlined. The past really did exist, but we can only ‘know’ that past today through its texts, and therein lies its connection to the literary. If the discipline of history has lost its privileged status as the purveyor of truth, then so much the better, according to this kind of modern historiographic theory” (Hutcheon 10).